Evan Binkley, contracted Covid 19 at his job as an Art Teacher in an international school. He was taken by helicopter from his home in Cheung Chau to Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital. After 48 hours observation, when it was determined that he was unlikely to have serious symptoms, he was transferred over to the newly completed North Lantau Infection Control Centre Hospital. There, in a room with up to five other people who contracted the virus from the Ursus Gym outbreak, he spent another 19 days. A stream of consciousness painting mostly completed at Eastern Hospital He brought with him some sketch paper, a few markers, and watercolor paint, with the idea that he may need to teach art classes for the school online. This paper, paint and pens ended up being his savior. Painting was the one thing he could do to keep himself sane while waiting day in and day out and watching eight different roommates come in and then get released. Concentrating in preparation for the test. He painted on every scrap of paper he had available, and as he began running out of proper drawing paper he started painting on the paper towels available in the room. This paper allowed him to produce various interesting effects that in some ways reflect the look of traditional Chinese paintings on rice paper. Landscape on paper towel The 163 paintings he produced cover a wide range of themes, from fantasy to frustration. One notable motif is the stainless steel and glass box that was the portal through which all provisions and gift parcels passed and acted as his main physical communication with the outside world.

“When I don’t know what to do, or think, or feel; I draw.

When I am exhausted mentally and can’t concentrate even enough to read or play an instrument, though I still feel a compulsion to move; I draw.

When I can’t focus on the thousand things I ought to be doing, and yet can’t imagine wasting a few precious hours of this short life by being idle; I draw.

When I enter a state where words and sound can’t congeal into anything meaningful, yet I need to sweat out the mental fever that frequently attacks me; I draw.

I draw a lot.

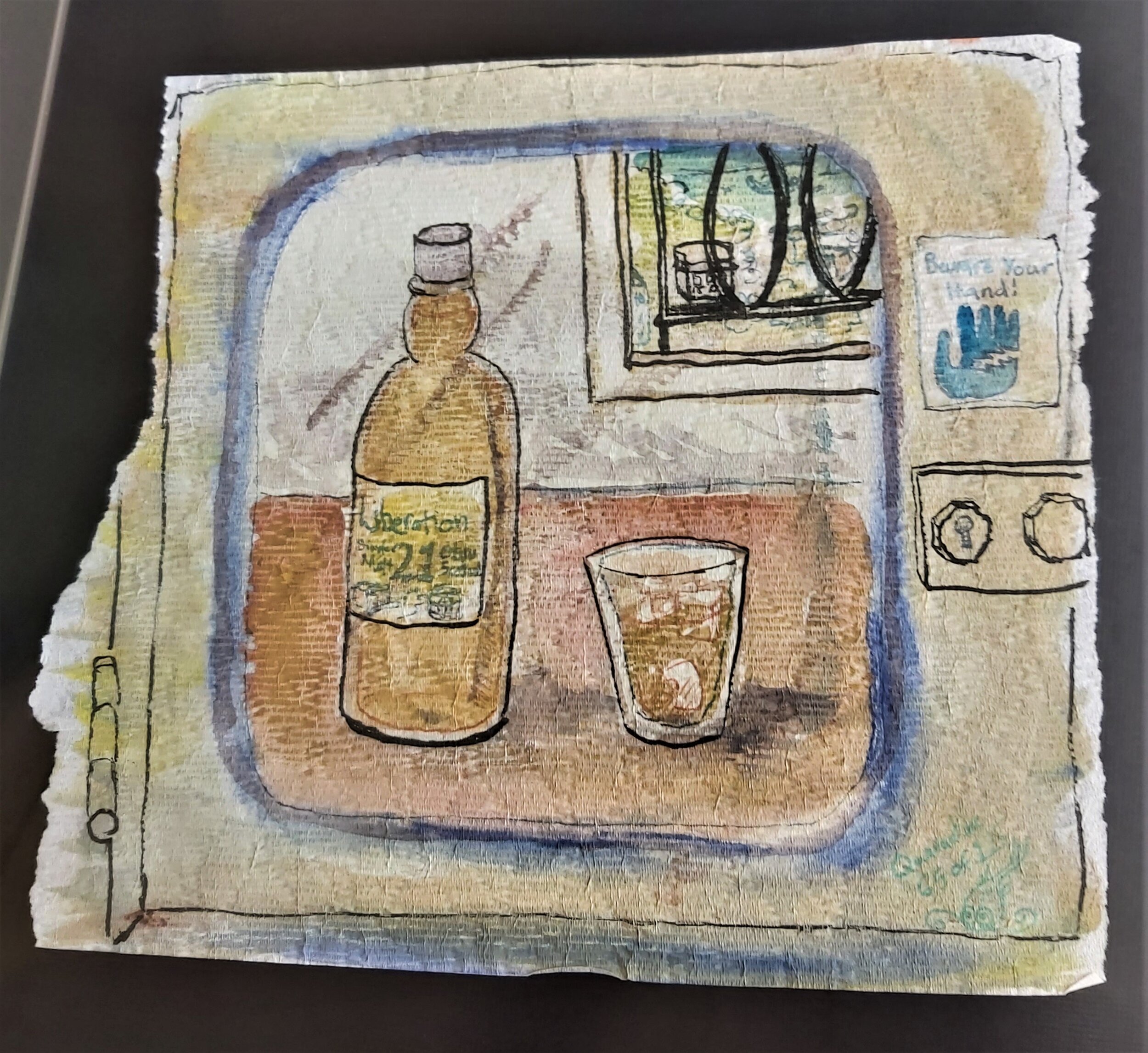

I spent 21 days locked up in an infection control hospital with asymptomatic Covid 19 (or possibly extremely mild symptoms). The first week was spent worrying how the virus would affect me or that I gave it to someone else. The rest of the time, I spent thinking every day would be the day I would be allowed to go home. The nature of this situation meant that for 21 days I was in my drawing state of mind.

Fortunately, of all the things I failed to bring with me, I remembered to bring a couple brushes, a palette, a few tubes of paint, some markers, and some paper. And during the mental roller coaster, I created 163 images (at last count). Few, especially at the beginning, of these images were meant as an explicit statement or documentation of anything in particular. They were stream of consciousness expressions intended to soothe my soul.

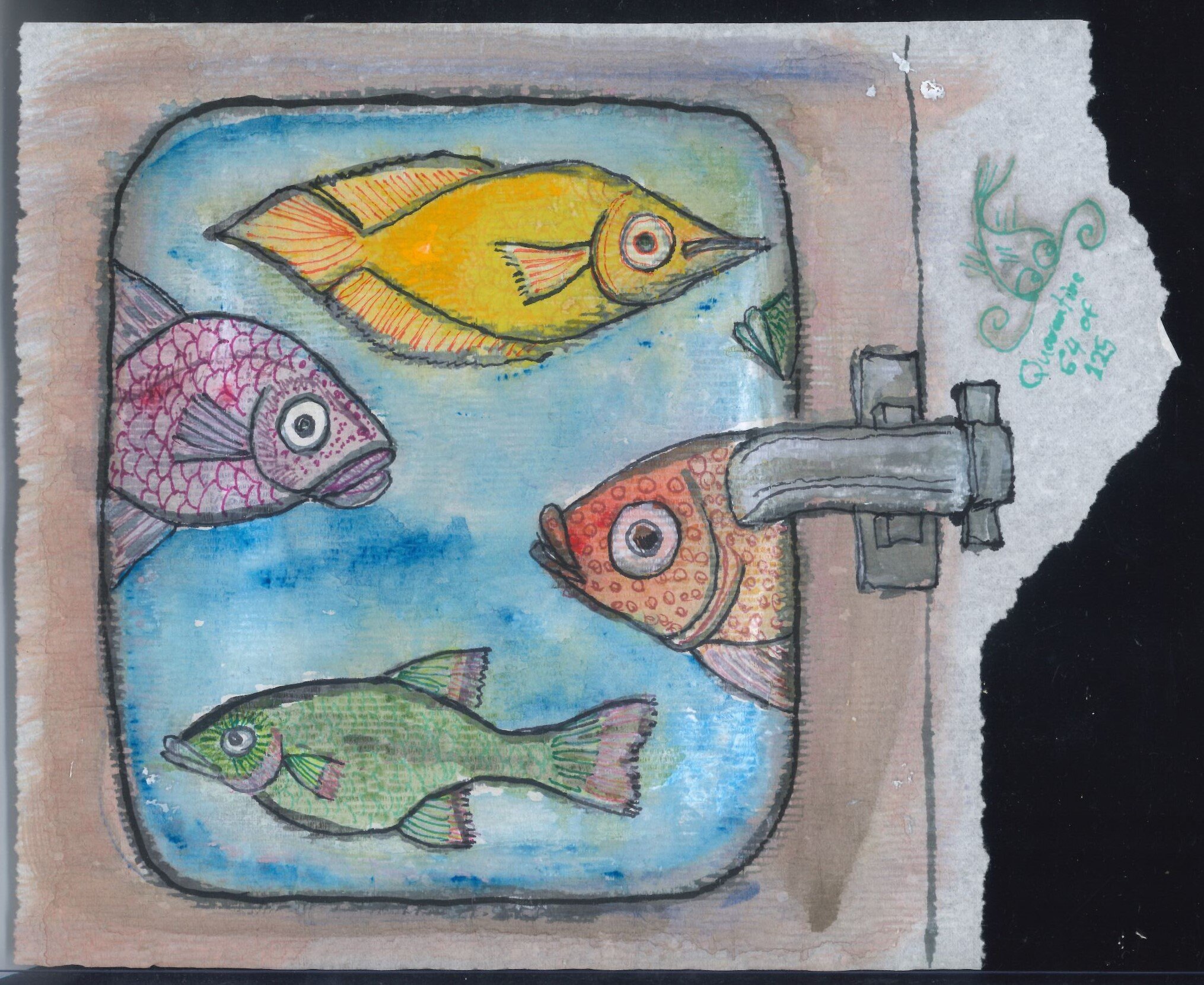

As time went on, themes became more apparent. I did some work that more specifically documented the characteristics and imagery of the circumstances. The ‘magic box’ through which we received all of our food, test kits, clothes and parcels from the outside, seemed to me, and my roommates a very poignant symbol of our surreal predicament.

7:30 am. A jolly but dystopian electronic melody plays over a loudspeaker, sounding not unlike a phone's wake up alarm, but louder and consequently more executive. A nurse's school teacher voice tells everyone first in Cantonese than in English to get up and check our own vital signs, before breakfast, at the little station that has Bluetooth powered blood pressure, oximeter and thermometer. These high-tech, PPE waist preventing gadgets upload or statistics at the pace of one who hasn’t had coffee in a week. My roommates and I have now learned not to delay this procedure or we risk hearing the same message again. If we still fail that, we end up getting a personal call from the haggard sounding personal intercom. Talking on the intercom is a kind of punishment for all involved because no matter how much annunciation either side attempts, no one really knows what the other person is saying.

The view from the large window at the selfserve vital signs station is almost like a mirror. It overlooks a building that I can only guess looks exactly like the building I'm in except that much lonelier because no one is in it. It’s almost like a warning that if you don't pass your ‘I’m no longer contagious’ test, you will be the only person left in a big sterile room. The North Lantau Infection Control Center was purpose built just for this pandemic, and by the modular construction of it, appears destined to be taken down the minute the threat of Covid 19 is over.

We are the very first people to use this room. Everything is fresh and lacks the ‘been coughed on for decades’ look of a typical hospital ward. It is equipped with all kinds of gadgets to prevent surface transmission. I can imagine the designers of this space working with a fervent sense of mission to show what man united with government can achieve when joining forces in epic battle to slay one of nature’s most terrifying forces. There are sinks that dispense water based on movements both real and imagined (sometimes turning themselves off and on all night long). There are loyal bureaucrat paper towel dispensers that dispense exactly one square that has been blasted by UV light on exit, and refuse to give another until the last has been removed. There are toilets that flush when you do the correct dance moves in front of them. There are Ipad-like tablets behind each bed to inform of food allergies and other individual patient needs and a central one to receive our vitals. There are two automatic doors on sentry duty, intentionally at right angles to each other and never to be opened at the same time.

These doors are the only way in and out of the room. They guard a kind of ‘mud room’ (that might be a very obscure midwest farmhouse feature) that allows the staff to take off their dirty (contaminated) PPE after the dirty air has been sucked back into our room. The ‘mud room’ has a mirror that, if you patiently pay attention, will occasionally let you see what the nurses and cleaners’ mouths, chins and noses look like. Seeing in the flesh the face of the opposite sex after a certain length of stay in a room of only one gender somehow feels almost like voyeurism.

There is a ‘magic box’ going through the wall next to a telephone. This box, maybe around 20” x 20” x 20”, has two heavy doors that looked like a cross between the kind on industrial freezers and those on microwaves. One door opens to the inside of our room and the other opens outside to the hallway. There is a wide beam of UV over each threshold. This was how we received things from the outside, like our meals and gifts from well wishers in the free world. Over time, when we heard the doors on the outside open, we would have a Pavlovian rush of excitement, and would try to resist the urge of rushing to it like fish to the surface of an aquarium when they see their carers pick up the food container.

The menu, if you like local cuisine, was surprisingly ok. This likely was because it was catered from the currently underused airport restaurants, rather than the product of a hospital kitchen. I actually gained weight. The fare that my wife, children and co teacher dealt with for 14 days at the illustrious Penny Bay government quarantine center was, by all reports, a very much less palatable. Thus they were thoroughly punished for being a close contact of me.

I won't say that my Covid 19 experience is the worst, or even bad in comparison to what so many have suffered. It was actually quite a light sentence for having met the little villain. But that's not to say it wasn't it's own kind of misery. Even at the best of times it was surreal. The mental and emotional toll and bodily atrophy complications took weeks to recover from.

I never, to my knowledge, got sick. I felt like hell the first week, but that could easily have been because I was stressed and to a certain extent, terrified. Terrified my body wouldn't be able to fight the monster. Terrified that I had given it to a neighbor who was elderly. Terrified of all the things I was unable to address while locked up. Terrified that people would hate me for putting them at risk.

This terror of being a pariah was especially pronounced because there was an official press the day my test came back positive that would easily identify me to everyone who knows of me in the community in which I live. If they weren’t aware of the press release, then they also got an alert on the tracking app that let all of the people in Cheung Chau (a small island I have live on 16 years and where I worked as a primary school teacher for 13 years) know the exact address of the 47 year old male foreigner who caught covid. I got a lot of messages the first week, mostly, but not exclusively, from well wishers and folks offering to help. I was also the source of much gossip, mostly speculating on how I must have caught it from cavalier behaviour.

How did I catch it? Most likely from about 10 minutes of computer and paperwork help from a colleague who caught it from someone else and didn’t know it. Fortunately I found out about my potential exposure early enough that it seems I did not pass it to anyone else. This is something for which I am eternally grateful and can be counted as a consequence of a system that mostly works. Albeit a system that is not particularly pleasant for the infected and the people close to them.

After the first week there came the anger and frustration, justified or not.

There are only two ways out of hospital quarantine in Hong Kong. The most likely is that a blood test reveals your body has developed antibodies, and thus the health department views you as not being contagious. The other is a test of virus content in your saliva that comes back negative two days in a row. Hong Kong’s standard for being not contagious, and thus free to leave the hospital, is very high. The WHO and the CDC advise that 10 days after testing positive for covid a person’s ability to pass on the virus is so minimal as to be virtually not contagious. The Hong Kong CHP views no risk of spread as the only acceptable standard. Thus even the definition of a negative viral load is higher than elsewhere. A viral load CT score of 35, is considered negative in most places. A score of 35, to my limited understanding, means that they put your saliva through a centrifuge 35 times before they found the virus. The CHP’s standard is 40. So if they spin you spit 40 times and they don’t find anything then you are negative. Unlucky for my hopes of going home, I had a CT score between 35 and 40 for most of a week.

Protocol says that you should get your blood tested every third day and your saliva tested every other day. Thus the first time they test a guy’s blood on the third day and he is set free, it occurs to him and everyone else in the room that if they had tested him 2 days earlier, he might not have spent two extra days in the hospital. So, by a week in, everyone gets into the same routine. We wait for a morning call from the doctor. Then after he or she asks you about how you're feeling and tells you your previous nights test results, (which you already know because you harassed the nurses to tell you the night before) you start cajoling, begging, harassing, and arguing to convince the doctor to break protocol and give you both tests that day. It’s a conversation you’ve been working on all night and morning since your last result.

Sometimes you win and get the tests. Sometimes you don’t. The next hour is spent discussing tactics, successes and failures with your roommates and how you are futilely going to try not to get your hopes up that you will get out that night. Then sometime around 5pm you call the nurses’s station and find out you don’t have antibodies. At 7 or 8 pm you call to find out your saliva is a CT score nearly, but still not, negative. Inevitably, you get depressed and try to fall asleep early, while thinking about how to convince the doctor to give you another 2 tests in the morning. Then some time in the middle of the night, you wake up and do fruitless Covid internet research on why you are still there and how you can get out sooner. It becomes an emotional roller coaster where you try to control the only thing you have any hope of controlling, which is convincing the doctor to test you.

Why? 163 out of 125.

Sometime around the 17th day I tested negative. Convinced I would test negative again the next day, I started packing up in the morning. I numbered all of my paintings based on what I had achieved at that point, which was 125. I attempted to roughly number them in order to when I did them. That night I got a CT of 36, a number that is only positive in Hong Kong. My frustrations boiled over and it was easily the worst night I spent in the hospital. Then at some point, in my feeling of helplessness, I went back to painting as my only therapy. I decided that numbering 126 to 163 out of 125 was in a way more meaningful, as it represented the experience of feeling robbed of my freedom, and the unanticipated 4 day encore of my captivity.

I watched many roommates come and go. It appears that if you get symptoms; loss of taste, coughing, fever so on, you quickly develop antibodies and get free. It seemed most people get out in 10 to 14 days. Only one of my roommates, and I, never had any obvious symptoms, thus both of us got out much later, when we finally tested negative two days in a row. He had the misfortune of being there longer than me. Apparently about 10 percent of people never develop antibodies, likely because their body didn’t need that part of their immune system to fight the virus. It is possible I would never get antibodies without a vaccine. Word of mouth says that one unlucky patient took 51 days to test negative. I can’t imagine how that felt. If I had been told at the beginning I would be in for 21 days, then the experience wouldn’t have been as stressful, but I wouldn’t say that I would have preferred it that way.

I do have to say a special thank you to the nurses that did some little things for us to make the stay less miserable.”

Evan Binkley (From Ohio, short term New Yorker, long term expat in Cheung Chau, Hong Kong) is a multi media story teller who shirks the clean, perfectionistic and tech based current trends and relishes hands on chaotic fraternizing with repurposed materials and implausibly functioning designs. He strives for the looseness of the margin doodle, while embellishing every free space with unexpected accoutrements. These days he primarily makes instruments marginally defined as ukuleles, turns hand drawings into animation, and tells empathetic and often humorous tales of the characters he meets in his daily life using poetry, paint, and song.

冰藝雲 (出生於美國俄亥俄州, 曾短暫在紐約發展, 現正長居於香港長洲) 是個多媒體藝術家。 他摒棄以科技主導、 乾淨俐落、 完美無誤的潮流, 偏愛於用雙手以舊有物料拼砌出狂野的東西, 製作品看起來似沒有實際用途, 但實際上是有功能的。 繪畫時盡量隨意, 同時注重在每處空白位置加上意想不到的所需陪襯。近期他主要的活動和製作有: 手作夏威夷小結他、 將手繪圖畫變成動畫, 並把日常生活中遇到引人共鳴又多屬有趣的故事化成詩、 畫和歌曲。

Contact here if you are interested in purchasing work by the artist and we will help connect you.